Research

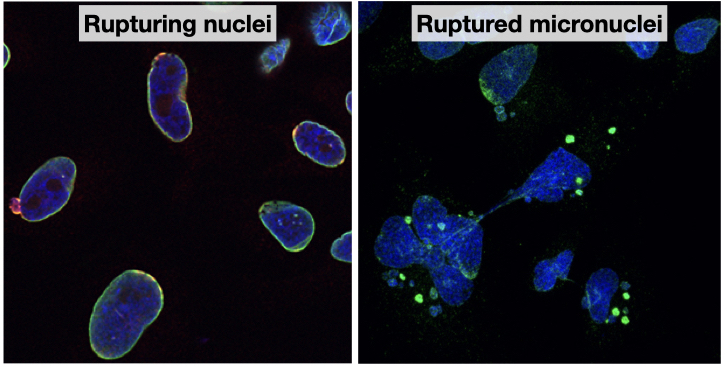

One of the principles of eukaryotic biology is that membrane-bound compartments are essential for complex multicellular life. The nuclear envelope regulates interactions between proteins and DNA and ribosomes and mRNA, allowing near infinite variations in cellular responses and signaling. However, recent work across multiple domains of life has demonstrated that cells have a remarkable tolerance for losing nuclear compartmentalization, and that this may even facilitate essential behaviors, including cell migration and senescence. Nuclear rupture is not without its costs, though. Even short disruptions of the nuclear membrane can cause extensive DNA damage and trigger metastatic signaling in cancer (Nader et al., Cell, 2020). Persistent rupture of nuclear membranes that form around missegregated chromatin, called micronuclei, can cause massive genome rearrangements that substantially alter gene expression in a single cell cycle in addition to stimulating inflammatory and invasive signaling (Zhang et al., Nature, 2015, Papathanasiou et al., Nature, 2023, Agustinus et al., Nature, 2023, Ly et al., Nat Genetics, 2019, Shoshani et al., Nature, 2021, Mackenzie et al., Nature, 2017, Harding et al., Nature, 2017).

Despite these important impacts on development and disease, we are still at the beginning of understanding the mechanisms driving nuclear membrane rupture and repair and how these processes affect cell behavior. Many classes of human disease, including cancer, neurodegeneration, auto-immune diseases, and laminopathies are characterized by changes in nuclear structure and integrity, but in most cases the connections between changes in nuclear morphology and disease pathologies are unclear. Our lab combines new cell-based tools with cutting-edge microscopy and image analysis pipelines to define the molecular mechanisms underlying nuclear membrane dynamics with the goal of using this knowledge to understand how nucleus integrity loss contributes to human disease.

© 2025 Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.